A (Very) Brief Introduction to László Krasznahorkai

The Berlin based Hungarian laureate of the 2025 Literature Nobel Prize has a reputation for being difficult. Yet he is a fantastically fun read and is well worth the effort. Where to begin?

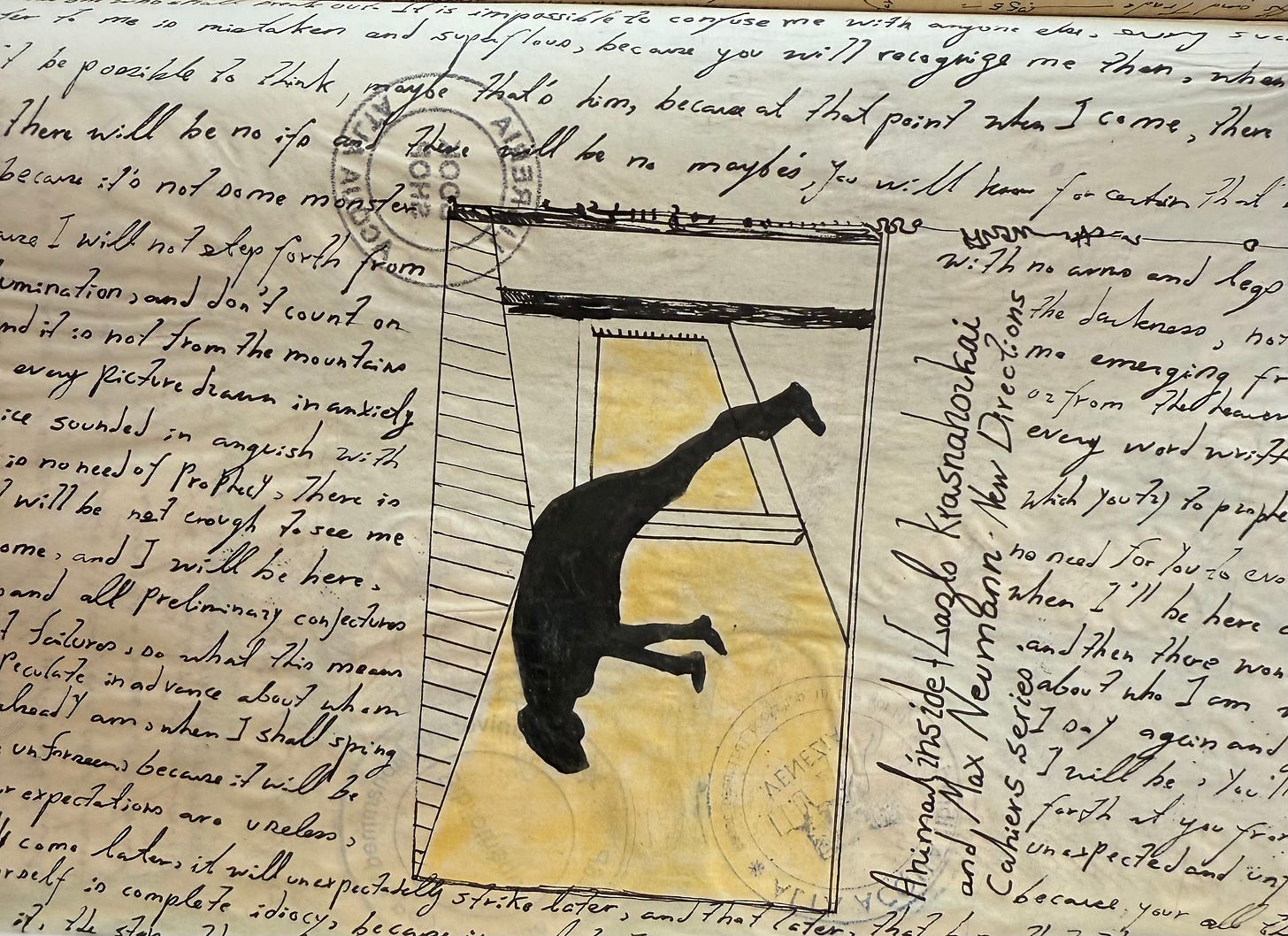

(My daybook page from 2011- ink and watercolor copy of a painting by the German artist Max Neumann which illustrated László Krasznahorkai’s AnimalInside”. My review of the short fiction from that time: “Hungarian Modernist László Krasznahorkai’s Inner Animal” in the Forward.)

As I wrote yesterday - Hungarian László Krasznahorkai being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature is excellent news. It may yet be that our civilization’s print culture and its rituals will be able to survive the oncoming decades of domination by the image. As well as the sudden return of communication via orality (the stream and podcast). If that is to be the case, the literati, hipsters and critics of the future will now be spared having to add Krasznahorkai’s name to their lists of great writers (Tolstoy, Borges and Proust, McCarthy) who were cheated. For once kudos to the good people in Stockholm. He has been on the betting odd sheets (standing at 33 to 1 a few years ago) for around a decade and a half.

The year 2011 was when I published my review of the New Directions Press translation of “AnimalInside” (by the supple Ottilie Mulzet; it also featured a preface from Colm Tóibín). 2011 marked the moment in which Krasznahorkai, who had long been celebrated in European circles, made his entry into the consciousness of Anglo-American readers. His Satantango was about to be published in English. Thus giving lovers of Béla Tarr’s seven and a half hour long classic a chance to read the source material (if they did not know German).

The critic James Wood published “Madness And Civilization: The very strange fictions of László Krasznahorkai” in the summer of that year in the New Yorker. That very influential piece -Wood was arguably America’s most influential practicing critic at the time - introduced Krasznahorkai to Americans.

Wood published an appreciation of that moment in the New Yorker yesterday:

“(In 2011) only two of Krasznahorkai’s novels were available in English—“The Melancholy of Resistance” and “War and War,” which had been published in Hungarian in 1989 and 1999, respectively. Krasznahorkai was already a European phenomenon, especially in Germany, where he was living and where most of his work had been translated. There it was common to hear him described as a likely future Nobel laureate, but, with so little to go on in English, such rumors had the status of palace gossip. Still, “The Melancholy of Resistance” got handed round like superior samizdat. It was Hungarian; it had a superb, mournfully grandiloquent title (hinting knowingly at both the importance of resistance and its inevitable exhaustion); and it carried praise from W. G. Sebald and Susan Sontag.”

The following spring (2012)- “Satantango”, which was the Hungarian’s bleak first work would be published with a translation by the great poet and translator George Szirtes. It was very much a novel of late Communist times. The long essay review of Krasznahorkai’s book in the London Review of Books by Jennifer Szalai further cemented his reputation in the anglo sphere. Szalai’s essay “Where Forty-Eight Avenue joins Petőfi Square” and the masterful Wood piece in New Yorker are great foundational previews of the work- they also built on one another:

“James Wood, writing in the New Yorker last summer, began by placing him in the capacious context of such postwar avant-garde novelists as Thomas Bernhard, José Saramago and David Foster Wallace, only to acknowledge that, despite a shared affinity for ‘very long, breathing, unstopped sentences’, Krasznahorkai was ‘perhaps the strangest’ of them.”

Many readers who want to try Krasznahorkai have been asking which novel to start with- The short answer is that The Melancholy of Resistance or War and War are good. My own advice to the fledgling Krasznahorkai novice is to ignore the commentary of both the philistines and snobs currently filling up social media. Krasznahorkai is simply magical - even if the unceasing and never ending sentence (the period/hard stop is for god alone he famously explained) is hard for you to follow at first.

Krasznahorkai is also important as an exponent of the post-Communist Central European authorial turn to surrealistic contortion- (proto Post-Modernist and parabalistic stratagems) as they strove to assimilate the traumas of the war- while being stuck between Scylla and Charybdis of Fascism and Communism. This is a Calvino tale - if Calvino was a Central European beset by a very dark vision. Sure -the novels are laced with dystopian existentialist darkness. But Krasznahorkai was part of a generation of late-Communist and post-Communist era European writers who were writing novels that served as humanistic escape portals from that existentialist morass.

To get a sense of Krasznahorkai’s humanism one might start with this interview with the novelist Hari Kunzru in the Yale Review. It was conducted amidst the murmurings this spring that Krasznahorkai would finally receive the prize.

Krasznahorkai discusses his views on art:

“Art is humanity’s extraordinary response to the sense of lostness that is our fate. Beauty exists. It lies beyond a boundary where we must constantly halt; we cannot go further to grasp or touch beauty—we can only gaze at it from this boundary and acknowledge that, yes, there is truly something out there in the distance.”

A much longer and more textured conversation is his “Art of Fiction” interview with the Paris Review from 2018.

However, of the various overviews of the oeuvre now appearing all over the place - I would heartily recommend the one from my critic friend David Auerbach:

“It is limiting to see The Melancholy of Resistance as a Communist allegory, for even as it relates to these events, it relentlessly confuses all possible interpretation of them. It is in the tradition of perverse authors like Kafka, Kleist, and Ingeborg Bachmann, but also Joyce, Goethe, and even Dante, who all pushed against the limits of the received ideas of their time to construct a more autonomous world in the “spiritual space” of which Krasznahorkai speaks. Contemporary reality becomes mere material for deeper, ambiguous parables.”

I myself have not yet had the chance to read Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming (2019) - the final installment of Krasznahorkai’s tetralogy. I will now be spending (parts) of the rest of this reading year with Satantango (1985), The Melancholy of Resistance (1989) and War and War (1999) in their original order of publication- which had not yet been possible when I read them as a student in New York and a graduate student in Paris and Venice. It is always an obsessive pleasure to read all of great writer’s books in a row one after another.

Thank you Vlad for this pithy, useful write-up. I only learned of Krasznahorkai last year, and have decided to read his works in order, as you mentioned at the end of your piece.